Distributional Uncertainty: Aleatoric or Epistemic?

(for more about distributional uncertainty and distributional shift, read this post).

The two types of uncertainty

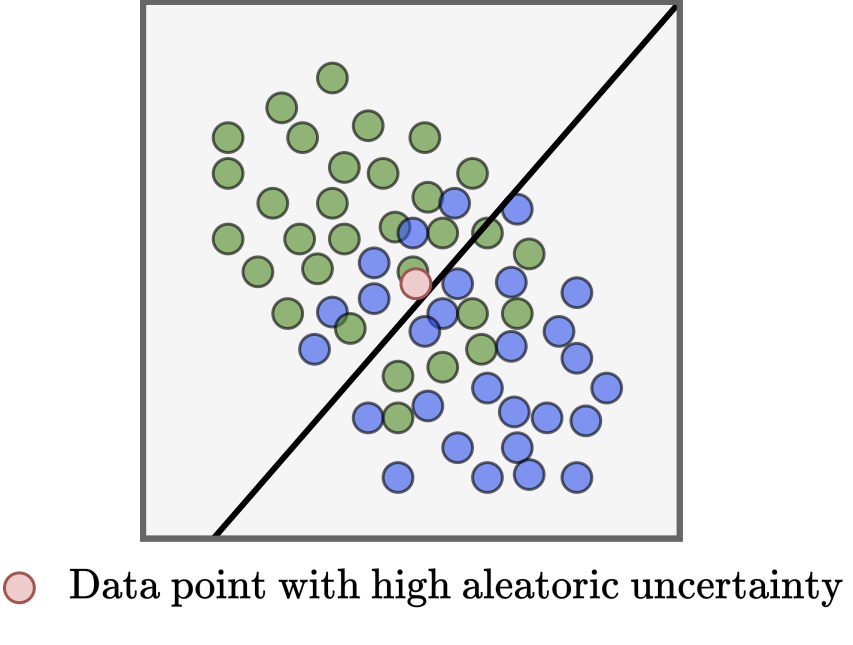

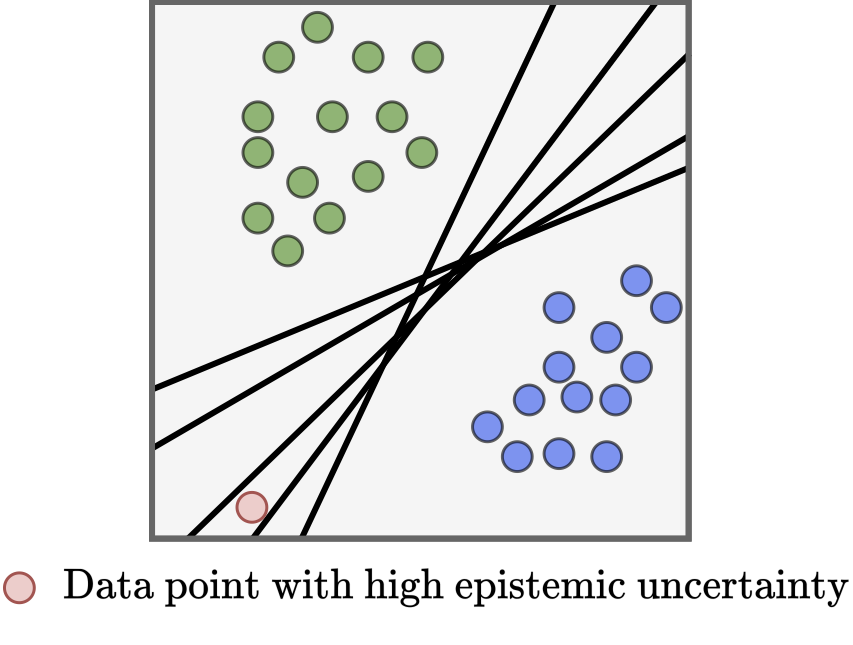

Uncertainty can be investigated by dividing it into two types: epistemic uncertainty and aleatoric uncertainty. Uncertainty is classified as epistemic if it is theoretically possible that it can be reduced by the modeller (by which I mean the person designing the model). For example, we can imagine the modeller trying to collect as much data as humanly possible, or receiving the design of the ideal architecture for a neural network through divine revelation. If these efforts reduce the test error to zero, then we can say that only epistemic uncertainty was present in the test data. For this reason, the presence of epistemic uncertainty is seen as a deficiency in the model parameters, and therefore is often known as model uncertainty.

By contrast, aleatoric uncertainty is uncertainty that cannot be reduced by the modeller. This means that despite all the modeller’s best efforts, it is not possible for them to reduce the test error to zero. This is because, for whatever reason, there is too much ambiguity inherent to the test examples and so it is simple impossible to accurately classify, regress or predict correctly. Therefore data uncertainty is the name that is often used in the place of aleatoric uncertainty.

Why are these definitions useful?

The first reason is that presence of epistemic uncertainty versus aleatoric uncertainty (and vice versa) tells us something different about the problem we’re trying to solve. A key example of this is active learning, where the model finds itself maximally-informative data points from which to gain a better understanding, and is therefore only interested in epistemic uncertainty. Examples of aleatoric uncertainty are, by definition, uninformative in this context.

Secondly, these definitions allow us to breakdown the problem of uncertainty estimation into two separate sub-problems, namely: epistemic uncertainty estimation and aleatoric uncertainty estimation. Due to their differences, the idea is that they can be better solved separately in this way.

Since epistemic uncertainty is only present due to the deficiency in the model parameters, methods for epistemic uncertainty estimation often investigate how the performance changes when a model is parameterised differently. If performance changes considerably for different parameterisations, then this is used as evidence that there remains uncertainty for this input from the model’s training.

By constrast, aleatoric uncertainty will exist over all possible model parameterisations. The evidence for its presence is therefore found by looking for instances where the performance is consistently low, and does not improve throughout training.

So what do we do with distributional uncertainty?

This poses some questions:

- Where does distributional uncertainty fit into this dichotomous framework?

- What method should we employ to estimate it?

When we consider the definitions above, we can quickly convince ourselves that distributional uncertainty is epistemic. The more training data we collect and train on, the fewer errors the model makes as a result of distributional shift $\rightarrow$ it is reducible.

But this isn’t perhaps the answer we wanted if we consider the computational cost of many epistemic uncertainty estimation methods. If we have to consider many different model parameterisations, then we have to do many model forward passes. This sounds doesn’t sound ideal from a latency or memory perspective.

Thankfully, these definitions can be slightly relaxed and we can rethink this from a more practical perspective.

So how should distributional uncertainty estimation work?

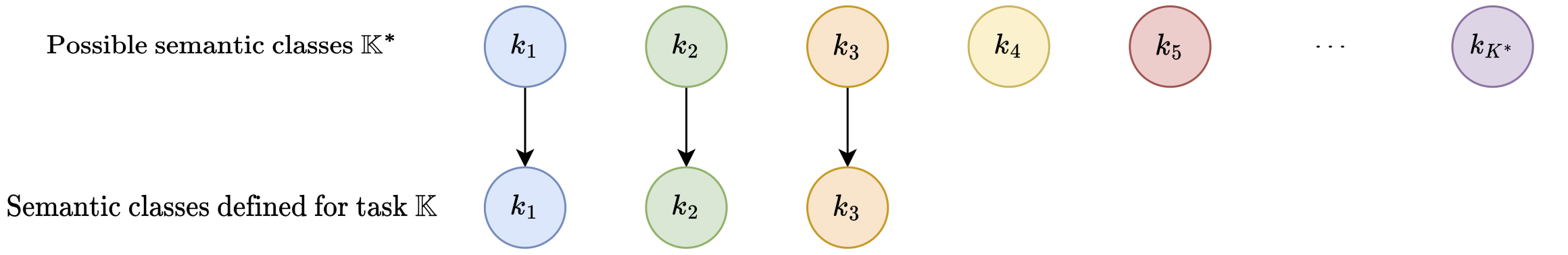

Suppose we are interested in image classification, where we have a three classes of relevance to us.

We do the normal thing and define a model that produces the probability of a given image belonging to one of these three classes.

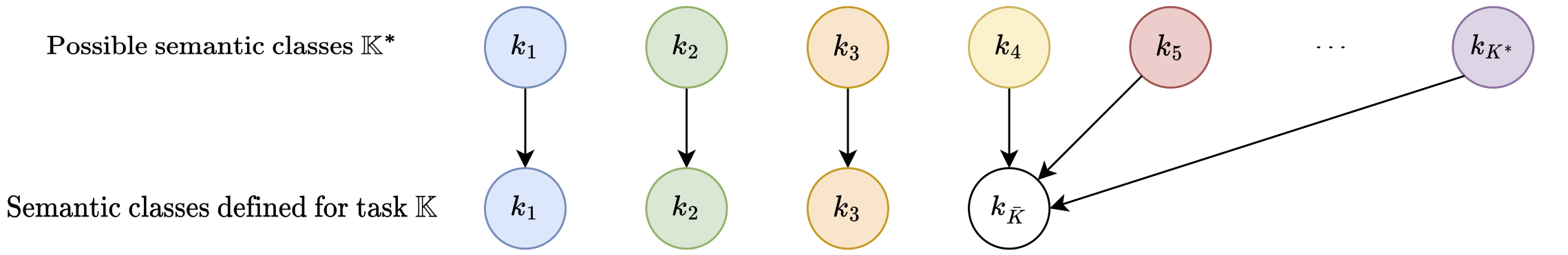

In this setup (seen in diagram), we ignore the fact that other classes exist, such as $k_{4:\inf}$, and just model the ones we care about, $k_{1:3}$.

Given this model definition, it is impossible for the model to correctly classify a test image as the correct class if its ground-truth class is not one of $k_{1:3}$. Therefore, the model could be enormous, with a highly effective architecture, and trained with one billion images, and it would still make mistakes on classes $k_{4:\inf}$. For this reason, it is only reasonable to consider uncertainty caused by unknown classes (i.e. distributional uncertainty) to be aleatoric in this context.

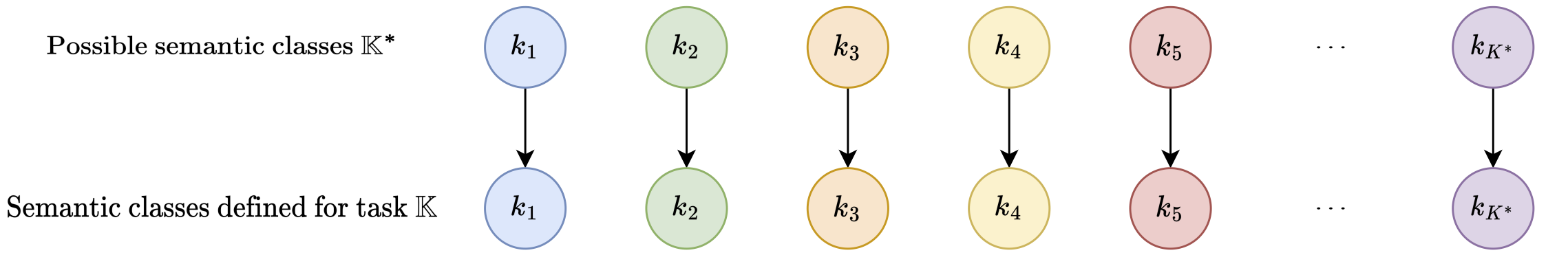

If we were unhappy with this realisation, then we could try and turn uncertainty due to unknown classes into epistemic uncertainty.

One way of doing this is to make the effort to model all possible semantic classes, for example by doing zero-shot classification like in CLIP.

Now, the model definition is such that test error could conceivably be zero under idealised architecture, dataset and optimizer conditions. For this reason, it is only reasonable to regard distributional uncertainty as epistemic once more.

An alternative, and perhaps more tractable, formulation would be to introduce a superclass named $\texttt{undefined}$ or $\texttt{void}$ or $k_{\bar{K}}$.

Again, in this case uncertainty due to unknown classes is reducible by including training data for the undefined class $k_{\bar{K}}$.

So where does this leave us?

Practically speaking, we can think about determining whether distributional uncertainty is aleatoric or epistemic is a function of the specifics of how the model has been defined.

From the perspective of low cost inference, this is good news as it raises the possibility of using single-pass aleatoric uncertainty estimation methods. By framing distributional uncertainty as inherent to the data, we can use out-of-distribution training data to learn to detect it instead of performing a potentially costly investigation into the model parameters.

Let me know if you have any thoughts about this: dswwilliamsworkspace@gmail.com